The municipal environment often includes barriers that exclude people with restricted mobility. These barriers may be the result of natural topography, historic planning, deterioration of the urban environment or planned and unplanned maintenance. Some of the barriers may not be known to the local authority.

People with mobility impairments are often on the frontline when it comes to negotiating these obstacles, and often have their own knowledge and strategies in negotiating and circumventing them. This is a resource that could be invaluable in helping others who face similar challenges, as well as helping local authorities identify where interventions need to be made.

Mapping Mobility Stockport aimed to create a mobility map of Stockport town centre by working with Disability Stockport and Age UK Stockport to crowdsource geospatial data for the areas that these communities regularly use, the routes they take to access these areas, the obstacles and barriers they come across, and the things that work well.

As most of this information is contained tacitly within the communities themselves, we designed a series of workshops which would help share this knowledge. We wanted to ensure that we weren’t doing or designing FOR these communities, but WITH them, directly drawing upon their lived experience, so we co-designed a series of workshops and outdoor mapping expeditions with members from Disability Stockport and Age UK Stockport. Sessions were led by Open Data Manchester with Stockport Council.

Workshops were based around the Joy Diversion meetups that Open Data Manchester run throughout the year. In a Joy Diversion, participants use maps of Manchester and Salford from the 1800s, form teams and propose expeditions to explore the two cities. They venture out, find and map points of interest, before returning to share their findings. Although primarily a fun, family-centred event, these have been used by OpenStreetMap enthusiasts too, and the format provided a good starting point for the Mapping Mobility workshops.

To take into account the specific needs and requirements of the project participants, there were two types or ‘streams’ of workshops designed to account for different needs.

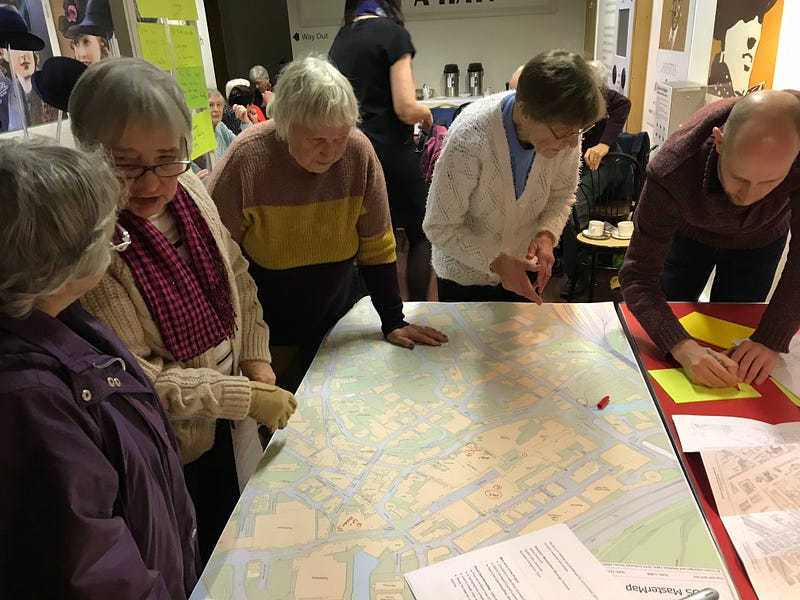

The first type of workshop consisted entirely of indoors sessions and made use of high-resolution printed maps provided by Stockport Council. We began by discussing areas and generating a list of obstructions and issues and beginning to identify particular areas of note. In between workshops, the facilitator took photographs of these to bring to the next session for clarification and to generate further analysis.

This naturally led into a deeper dive into the problem areas themselves. Participants began to share their experiences in more detail and describe routes that they take on a regular basis. These were marked down on the map and numbered. We wrote down details on Post-it notes with corresponding numbers. After each session, these features would be written up into a spreadsheet, with the identified spots photographed, brought back to a subsequent session for clarification and further investigation.

The second type of workshop consisted of outdoor expeditions with workshop participants, and it was from these that we sourced the most data and insight. Trips were weather dependent — due to parameters of the funding, the project began in January and finished in March, so we were at times rained or snowed off.

Participants were able to convey their experience of accessing Stockport across a broad range of impairments physical, neurological and visual. By organising individual expeditions, we were able to give more time and gather more in-depth data pertaining to each particular disability. Digital recorders were used throughout allowing participants to narrate their experiences during the expeditions.

From these expeditions, we gained some incredibly valuable insights. One related to the use of tactile paving, whilst useful for those with visual impairments, they can be a hazard for a wheelchair user, where the chair’s jockey wheels can become caught on the bump and cause the person to be thrown from their chair. So where tactile stretches the width of the paving guiding someone to a controlled crossing, it becomes hazardous terrain for someone in a wheelchair. In short, what is assistive for one person, becomes an obstacle for another.

Another observation from a participant was particularly enlightening: for most of us, we think of roads as a single location or a single route; for someone with blindness, each side of the pavement is a different terrain that needs to be learnt

This also led us to a further question- how can we map streets — roads, paths, kerb-sides, pavements — to make them more inclusive?